First published in San Francisco Magazine.

In this era of the locavore, menus no longer merely inform diners what they’ll be eating. They also tell the story—often as elaborate as a bildungsroman—of where the ingredients in a dish were raised. Those dry-farmed Early Girl tomatoes in your salad? They once lived in a field near Santa Cruz. Those baby Chioggia beets? Tugged from organic dirt in Watsonville, then transported to restaurants in a biodiesel-fueled pickup. That rosemary-rubbed hanger steak? It was once a cow roaming the hillsides of West Marin with no more hormones than its own pituitary gland could produce.

What you won’t find out as readily is precisely where the cow made the transition from cavorting weed eater to inhabitant of a restaurant’s walk-in. That omission is unfortunate, because where an animal dies is as integral to the definition of local food as where it lived.

Books like Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma encourage us to think more deeply about where meat comes from, educating us on the issue of grass-fed versus grain and about the benefits—both to animals and to the people who eat them—of livestock raised in verdant pastures, rather than in factory farms’ crowded, unsanitary conditions. We’ve learned to not assume that organic means small, local, or even ethical, and to ask where the animals we eat were raised and what they were fed. What we haven’t learned is to ask how and where they were killed.

That isn’t surprising. Even hardcore carnivores struggle with the act of killing. On the blog that he calls Offal Good, Chris Cosentino, executive chef of the restaurant Incanto and partner in the artisanal-salumi company Boccalone, posted a photo of himself holding fistfuls of goat entrails. An accompanying photo essay documented the disassembly of a cow that Cosentino helped butcher; he served the heart and liver at his restaurant, and its hide now graces the floor of his home. But Cosentino’s in-your-face presentation is infused with a schoolteacherly desire to illuminate the food chain, in both its savory and its less savory aspects. Slaughter, he says, is “a frightening thing. It brings on a massive rush of emotions—horror, fear, joy, pity. I cry every time I do it.”

But now, a small group of activists has taken up the cause of the slaughterhouse. Three years ago, Phyllis Faber (biologist and cofounder of the Marin Agricultural Land Trust) joined forces with business consultant Sam Goldberger (former psychologist, current antique-pipe dealer) in an effort to build a modern slaughterhouse in the Bay Area. The two believe that local meat processing plays a crucial role in sustaining the Bay Area’s agricultural viability.

“Farming in Marin and Sonoma,” says Goldberger, “is in serious danger of becoming a kitschy, unprofitable replica of a real industry. If it’s not profitable, it might as well be Colonial Williamsburg.”

Goldberger and Faber’s vision includes a new facility, called North Coast Meats, that would serve as a model for an integrated, efficient, and economically successful regional meat industry. They see it as a prototype for a new movement—let a thousand slaughterhouses bloom, if you will.

Armed with a $100,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce, the two are enmeshed in feasibility studies—a massive three-ring binder, filled with floor plans, 3-D computer renderings, and exploded diagrams, outlines their dream. The plans were devised with the help of Graeme Baker and Nook Yule, slaughterhouse designers from New Zealand. It’s no coincidence that that country’s success with regional slaughterhouses is what Goldberger and Faber seek to emulate in the U.S. In just a few decades, New Zealand transitioned from a large, centralized meatpacking system—not unlike our own—to focusing on small, clean, efficient slaughterhouses dispersed all over the country.

According to Goldberger and Faber’s plan, North Coast Meats would be equipped to dispatch close to 40,000 head of cattle a year, as well as lambs. Everything from the facility’s shape—a modified wishbone that would guide the cattle along a slight curve and make as few cow-spooking 90-degree turns as possible—to the holding pens to the chutes would follow guidelines established by famous humane-slaughter authority Temple Grandin. There would be no bright lights (cows don’t like shadows) and no mezzanine level (people walking above their heads makes cows nervous). The plant would practice job rotation (to prevent repetitive stress injuries and alleviate boredom among the workers) and offer profit sharing, and would house an anaerobic digester for making biodiesel out of cow effluvia. It would have its own cut-and-wrap facility so that meats could be aged and processed onsite, then packed and sold directly to restaurants and retail shops—something that Goldberger describes as essential to the operation’s profitability, and to its ability to pay ranchers a premium. In architectural renderings, the slaughterhouse exterior looks strikingly like a winery, complete with stucco walls, arched porticos, and cypress trees. The only thing missing is a yoga studio.

Ideally, North Coast Meats would be as close as possible to San Francisco. “I think it’s critically important that agriculture succeed near a metropolis of seven million people,” Faber says. “We can’t afford to have corn grown in Iowa, then shipped to Marin to feed animals that must be shipped to the Central Valley or beyond to be slaughtered. That’s just too much in terms of gasoline consumption, if nothing else. Too much in the way of antibiotic requirements. We need to think about food in a much more efficient way. And here in Marin, we have prime grazing land. Not prime soil—prime grazing.”

The ability to both graze and kill animals locally is a key component of what Michael Pollan refers to as the “re-solarization” of the food chain. The current industry standard is to feed animals grain grown with oil-based fertilizer, then use more oil to move them from ranches to slaughterhouses before sending their meat around the country to restaurants and grocery stores. Pollan advocates for a system in which livestock are fed solar-powered, non–chemically enhanced grass, then killed and consumed as near as possible to the place where they were raised. “Somehow,” says Pollan, “we have to make it possible for people who are producing meat locally to get their animals processed locally. This is one of the biggest obstacles to developing what everybody says they want, which is a vibrant, local food economy.”

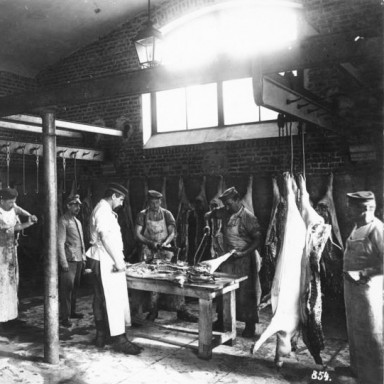

Slaughterhouses used to be far more local than anything Faber and Goldberger are proposing. Before refrigeration became widespread, animals were killed in cities because that was where the people were. Most San Franciscans have heard stories about cattle-filled railroad boxcars being unloaded near Butchertown (now known as Bayview/Hunters Point), and about Dogpatch acquiring its name from the packs of feral dogs that foraged the area’s streets, looking for slaughterhouse refuse.

Eater and eaten have grown apart since then. As slaughterhouses have consolidated (from 1976 to 1996, the number of federally inspected plants processing beef decreased by more than half), they’ve grown from facilities that killed fewer than 100,000 animals a year to ones that are designed to kill 10 times that many. Not surprisingly, these larger plants tend to develop where land is cheap and environmental regulations are lax—two features that don’t often apply to California. But even Wyoming, which is home to a huge ranching industry, doesn’t have a single USDA-approved slaughterhouse.

The current slaughterhouse system relies on cheap grain and cheap petroleum, and some claim its days are numbered. Subsidies have kept the price of cattle feed well below the cost of letting cows graze on grass. But now that corn-based-feed prices are rising (thanks to increased ethanol production), the gap between the two is narrowing. And as fuel becomes more and more expensive, the notion of running a slaughterhouse so big that it needs to pull in thousands of cattle from out of state to keep running at capacity begins to seem very strange. If current trends continue, it wouldn’t be surprising if smaller facilities, which for decades have operated so close to cities that it’s a marvel they weren’t turned into strip malls, may one day make out like bandits while big operations in Kansas, Nebraska, and Texas become ghost towns. But for now, until the economic winds shift more dramatically, small slaughterhouses located near big cities still struggle at every turn.

Back in 2006, a livestock and natural-resources adviser named John Harper suggested that Faber and Goldberger build their slaughterhouse in Ukiah. Though it wasn’t as close to San Francisco as they had hoped, Harper’s argument that “the timber industry is on hold, the grape industry is maxed out, and the Masonite plant is gone” convinced them. “We were innocently thinking, ‘Wow, good jobs for 45 people. They’ll be interested,’” recalls Harper. And the area seemed familiar enough with agriculture’s gritty realities to be amenable to the plan. The Board of Supervisors was friendly, the local ranchers were excited, and the land was affordable.

It was a disaster. Things seemed to be going well, but then they weren’t. A well-organized opposition materialized seemingly out of nowhere, objecting to the slaughterhouse on environmental, social, and financial grounds and quoting from the more grisly sections of Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation. Arguments that Faber and Goldberger were the good guys, with a plan meant to correct the problems that book outlined, had little effect.

“I know that eating meat is not going to stop anytime soon,” says Jan Allegretti, a dedicated vegan and animal-rights activist who led the opposition. “But there is no humane way to kill anyone. I couldn’t live here knowing that was going on.”

Many meat eaters joined the cause as well. That a rural area with plenty of livestock felt hesitant about allowing a slaughterhouse to move in shocked Faber and Goldberger, who see the project as part of a larger vision of food, community, and a self-sufficient economy.

It was a case of one California ethical system colliding with another, completely incompatible one. “It’s not a philosophical discussion for these animal-rights people,” says Faber. “It’s really much more profound for them.”

“I don’t think it makes any difference to the vegans whether this thing secretes only nectar and ambrosia,” Goldberger adds. “They simply don’t want any animal-killing in their vicinity.”

The two gave up on Ukiah but have continued scouting locations, though they’re understandably reluctant to discuss where those locations might be. Police asked Faber and Goldberger to cancel a recent public meeting with Sonoma ranchers because of rumored picketing by animal-rights activists, and local politicians have become skittish. “People are generally supportive,” says Goldberger. “The question is where to put it.”

“Everyone wants meat,” says Chris Cosentino, “but no one wants a slaughterhouse.” Everyone may be an exaggeration, but if only 3 percent of the population is vegetarian (as Vegetarian Journal asserts), and the average American eats 200 pounds of meat each year (as the USDA claims), that’s a lot of meat. According to California state law, any meat sold in a restaurant or grocery store has to come from an animal killed in a USDA-approved slaughterhouse—and those facilities are increasingly few and far between.

A handful of people are working to make this small slaughterhouse model viable. Sallie Calhoun is one of them. After making a bundle during the dot-com boom, she moved to Paicines, near Hollister, to focus on her true passion: native California grass. The kind once nibbled by hordes of elk and antelope roaming California’s savannas—until, as Calhoun succinctly puts it, “we shot all of them.

“I came from a farming family,” Calhoun tells me. “In another time, I might have gone right into agriculture. But if you were smart and female in the 1970s, you were expected to do something else. But this—the biology—is so interesting, so fascinating. It’s much harder than the high-tech industry.”

Calhoun discovered that the grasses she loved most needed to be grazed to avoid being choked out by denser undergrowth. She fell in with a group of holistic land managers who experimented with managing cattle as though they were wild animals.

When Calhoun decided she’d like to market grass-fed beef from her herd of cattle, she found herself driving 10 hours round-trip to slaughterhouses in Creston or Orland, only to find those facilities overwhelmed and extraordinarily busy. “I would show up with 10 head of cattle, and they would say, ‘Sorry, we can only do six.’ So I thought, ‘Maybe I can just open a small plant on our ranch.’” Then Calhoun discovered that although her land was zoned for agriculture, that zoning didn’t include a slaughterhouse permit. Vegetable processing may be fine, but animal processing is verboten.

After that plan failed, Calhoun found a slaughterhouse in Newman, a town 74 miles northeast of her ranch, that had closed several years earlier. Because the original structure had been USDA licensed, it was easier for Calhoun to rehab it than to construct a new building. The renovation was more extensive and costly than she had anticipated, but she eventually reopened the facility under the name Cutting Edge Meats.

Even with solid help and a good location (Calhoun is about two hours from San Francisco and four hours from Los Angeles), Cutting Edge Meats’ economic viability remains undetermined. Many ranchers in the area are from the old school: They’re more comfortable with unloading their cattle on a broker in Texas than with facing the culturally unfamiliar prospect of paying Calhoun to slaughter their animals, then having to deal with the task of marketing the meat themselves. In addition, a two-year drought has drastically reduced the number of cattle in the area—Calhoun herself has had to sell off 80 percent of her herd because she didn’t have enough grass to feed them.

There is one very successful small slaughterhouse in Northern California: Prather Ranch. Though it’s located 324 miles from San Francisco—in the town of Macdoel, north of Mount Shasta—the ranch has built a strong local following through its presence at farmers’ markets and its store in the Ferry Building Marketplace. It has also made a healthy profit selling cowhides to Collagen Corp., a now defunct company that extracted collagen from the hides and sold it to dermatologists and plastic surgeons. In the mid-’90s, Collagen Corp. paid for and built a USDA-certified slaughterhouse on Prather Ranch, thereby ensuring that Prather’s herd (as well as the people injected with the cattle’s by-products) wouldn’t be exposed to diseases or other contaminants the cattle could contract while passing through offsite slaughterhouses. For this reason, Prather’s facility is closed—only the ranch’s own herd can be killed there.

Prather Ranch has since branched out, selling livers, bones (one cow equals hundreds of bone implants), and pituitary glands to the pharmaceutical industry. The beef itself is simply the leftovers from these other, highly profitable endeavors.

Other local ranchers are not likely to be so fortunate as to acquire a medical-implant sugar daddy. Instead, most of the ranchers from Marin and Sonoma rely on Rancho Veal, the Bay Area’s last remaining slaughterhouse. Run by the 70-year-old Bob Singleton, whose father bought it for a song in 1966 when it was in bankruptcy, the building looks like a tool-and-die shop. Down the road, the Petaluma Village Premium Outlets beckon with offers of discount pants and casual office-wear sets.

When it was built 80 years ago, Rancho Veal was ideally situated to serve the region’s many dairy farms. Cows that failed to produce enough milk were sent there to be processed along with the herd’s male calves. In the years since, however, Rancho Veal’s central location has occasionally proved unfortunate: The facility has been firebombed twice.

It’s Singleton’s opinion that local ranching is gradually dying out. For years, he has refurbished and repaired Rancho Veal with equipment he’s scavenged from the slaughterhouses that have gone belly-up around him. Throughout Sonoma County, cattle ranches and dairies have given way to subdivisions and vineyards. Two years ago, Singleton sold Rancho Veal’s property rights to a real-estate developer. That deal fell through earlier this year, another victim of the mortgage crisis, and Singleton has kept his business going through his willingness to roam farther afield—snapping up veal and dairy cattle from as far away as Nevada and Twin Falls, Idaho. Rancho Veal now kills approximately 21,000 cattle each year—about half as many as Faber and Goldberger’s facility would.

David Evans, whose family has been raising cattle in Point Reyes for four generations, intends to submit a proposal to buy Rancho Veal. As the owner of Marin Sun Farms, a marketing label for local livestock producers, Evans sees a slaughterhouse as an ideal launching pad for an even broader exercise in branded collective retailing. He would like to redesign the existing facility at Rancho Veal, bringing it up to the standards Grandin established; potentially add an aging room and a small cut-and-wrap plant; and reconfigure the current setup to handle not only beef, but also pork and lamb. For the time being, he’s trying to round up some investors.

Mac Magruder, a cattle rancher in Mendocino County, hopes to see Evans succeed. Magruder believes that establishing this kind of local meat-processing plant is the most important factor in sustaining ranching—and, by extension, open space—in the Bay Area. “Slaughter is an issue that most people prefer to ignore and pretend isn’t part of the process,” he says, “but the public needs to understand that they can’t have the healthy meat they’re beginning to realize they want and need, unless there’s an infrastructure to provide it.”

Perhaps we’ve reached a point where meat-processing plants will begin to reinhabit urban regions—slinking back into cities like suburbanites looking for a shorter commute and better coffee. For a long time, we’ve defined the good life as distancing ourselves as much as possible from our food’s origins: living in purely residential areas, shopping at the supermarket, planting begonias instead of tomatoes. But there are signs that the future may be different. In the midst of the energy crisis, as Evans talks of reinventing Rancho Veal, and Faber and Goldberger move ahead with their feasibility study for North Coast Meats, it’s entirely possible that 90 years from now will look a lot like 90 years ago—a butcher shop in every neighborhood, and a slaughterhouse in every city.